The Art of Chess Variants

A show at the World Chess Hall of Fame and the joy of mixing it up

When my eight-year-old son stepped into the World Chess Hall of Fame & Galleries1 third floor show on “chess variants”, he gasped. The first thing he did was run to the three-player chess game so that me, Daniel and he could all play.

And this was a great instinct from Fabian. After all, three-player games are often marred by the inevitability of collusion (even when unintentional), a topic that I explored in a piece on the TV show, the Beast Games. And when it’s two parents and one kid, you can imagine that the kid will come out on top.

Fabian really liked all the variants, circling the room in excitement, challenging me in each one, some of which I did not know the rules of. A chess variant is a twist on the traditional rules, and can range from a minor change like “No-Castling Chess” (which bans castling) to the total chaos of “Crazyhouse”, where you can drop captured pieces back on the board.

The show by Shannon Bailey, chief curator at the Hall of Fame, contained popular variants that have stood the test of time like Chess 960/Freestyle Chess, as well as newer favorites, like Duck Chess and Laszlo Polgar’s “Star Chess.”

If variants are so exciting on the surface, why do so many of them struggle for popularity and viability? The vast majority of games played on the lichess platform were played in regular chess (over 98% in 2022).

I’ve thought a lot about this, and have seen the same effect in poker, where No Limit Hold Em remains supreme. Mixed games see spurts of popularity, but none have come that close to becoming the new default. And there’s a reason for that. People like being good at things. The more you play a format, the more you can have a decent “B-game”, and since many of us can’t help but play when tired or distracted, it’s comforting to have a baseline competency, especially in openings, or in the case of poker, opening ranges.

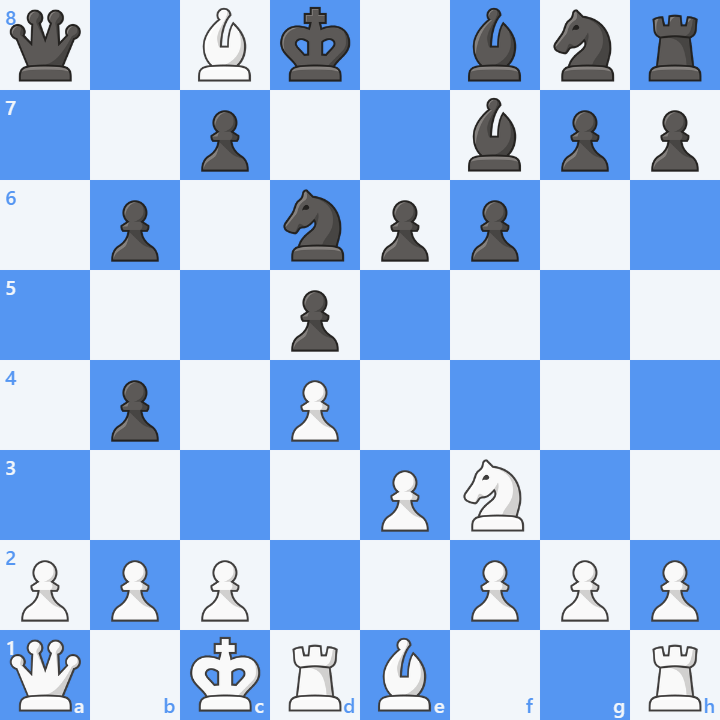

Vanilla chess allows hard working players to get a lot of moves rights, even if they’re not professional. Once you mix it up with chess 960 or wild variants like crazyhouse, accuracy rates plummet. For example, here’s a game I played the other day in chess 960 against a friend, who is around 2000. I’m playing White (apologies to my knight).

What the heck is it doing on a6? Seriously. Mistakes were made. I hoped to wiggle my way out of a poor position with 1.Nb4 threatening Ba6. Sadly it doesn’t work: Black has 1…a5!! when 2.Ba6 Qa8 3. Bxc8 axb4 and my poor bishop on c8 is trapped in a rare pattern that doesn’t often appear in “regular chess.”

As a chess poker player, I decided to take the risk that he wouldn’t see that key line after …a5. My position was so poor that it was worth gambling. And I was right! He missed it and my position recovered.

If we played regular chess, the first eight moves would likely be flawless recitations of our repertoires, and I’d never discover such a fun line.

Many chess players prefer to play well on an absolute scale, not just a relative scale. They want to make fewer mistakes and blunders, even if it means winning less often. You see the same risk aversion in poker, career and all areas of life. In some cases it’s just logical. One blunder can ruin 40 perfect moves, and chess rewards consistency. An especially apt metaphor for life these days due to the potential of social media algorithms to blow up errors: one big mistake is more likely than ever to ruin a reputation.

In finance, the risk of ruin often trumps profitable bets, which is one reason that the rich get richer (they can afford to make all those favorable bets that are too risky for people without a large bankroll) See my friend David Lappin’s piece on the “Kelly Criterion.”

But sometimes we focus so much on avoiding blunders that we’re afraid to try something new, and to have fun, the things that initially attracted so many of us to games.

The audience for chess variants is mostly chessplayers. With an audience that is often obsessed with the main course (regular chess), variants need to solve a pain point to capture and sustain interest.

Two variants do this perfectly, and that’s why they’ve remained top dogs in the variant universe.

Bughouse: This is an incredibly complex game with two-player teams. Partners give each other captured pieces, which they can then place on their own board to checkmate. Time is a crucial component of bughouse: when one player is winning on their board, the partner can often “stall” in order to secure victory.

What problem does bughouse solve?

Bughouse is the opposite of many stereotypes of chess. It’s boisterous, very social, and collaborative. Kids love to play it between rounds. Or at least they used to. I get the sense that bughouse isn’t quite as popular as it once was due to online chess and apps now taking up that downtime between games.

There’s a big push among parents to get their kids to play outside to get them off their devices. Maybe it’s time to start pushing bughouse for the same reasons.

For decades, the common wisdom is to tell kids NOT to play bughouse, as it will distract them from regular chess. But what is “regular” anyway? Go play bug!

Chess 960, also known as Fischer Random or Freestyle Chess: This one solves a very big pain point: chess has become so well studied and researched, that there are reams of opening theory on the regular starting position. Shuffling the pieces on the back row solves this, forcing players to think on their own from move one. I love the variant, and even played my first Chess 960 Simul this summer in London.

YAS Freestyle Queens: When Simuls Get Scrambled

While in London last month for the PokerStars Women’s Summer Festival, I played a simul unlike any that I’ve ever given. And that’s saying a lot, because I’ve given over a hundred simultaneous exhibitions in my career.

But neither of these variants are my absolute favorite of the most popular ones.

My favorite is a mixture of the two: chess 960 Bughouse.

Like chocolate cake with vanilla icing, it’s the best of both worlds. 960 bug is social and fun, and every game is different. In the ordinary bughouse position, we almost always go for the weak f7 square, while in 960 bughouse, you never know when or where your opponent might attack. But you’ll know something is coming.

Maybe we could all use a few more variants in our everyday lives, little twists in our routines that keep us from repeating the same openings over and over.

What’s your favorite variant?

I’m on the board of directors of the museum, which you should visit if you’re in Saint Louis: https://worldchesshof.org/

My favorite variant is Capablanca chess, with two extra pieces: the archbishop (a bishop-knight hybrid) and the chancellor (a rook-knight hybrid). I imagine there are opportunities for really pretty tactics if very strong players ever took it up (maybe that's what happened in the training games by Capablanca himself, in which he apparently quickly crushed his opponents). There is a video of this variant, there dubbed Gothic Chess, in which Susan Polgar plays the software developer Ed Trice, who apparently has a lot of experience in the variant. As I recall, Polgar simply traded off a pair of the weird pieces and proceeded to soundly beat Trice in a game of essentially ordinary chess on a bigger board.

I've been a huge fan of variants for 50+ years now. Began with bughouse, and continued exploring. One of my faves involves the smallest of changes that manages to nullify all of conventional chess's opening theory. Its starting position is played accidentally many thousands of times every year...only to be "corrected" at some point--depending upon a TD's decision. I don't even know it if has a name. Either White or Black should begin with their King's and Queen's positions switched. So it's neither conventional chess, nor is it a 960 starting position. Can I patent it? Name it after somebody?